Singapore's early beginnings intertwine fact and folklore – the city-state has been engaged in the pomp of ancient Malay empires, the intrigues of medieval trade, the bartering of European colonial powers, and the challenge of nation-building.

Here, we give you an account of Singapore's remarkable development throughout the centuries.

Colonial Singapore

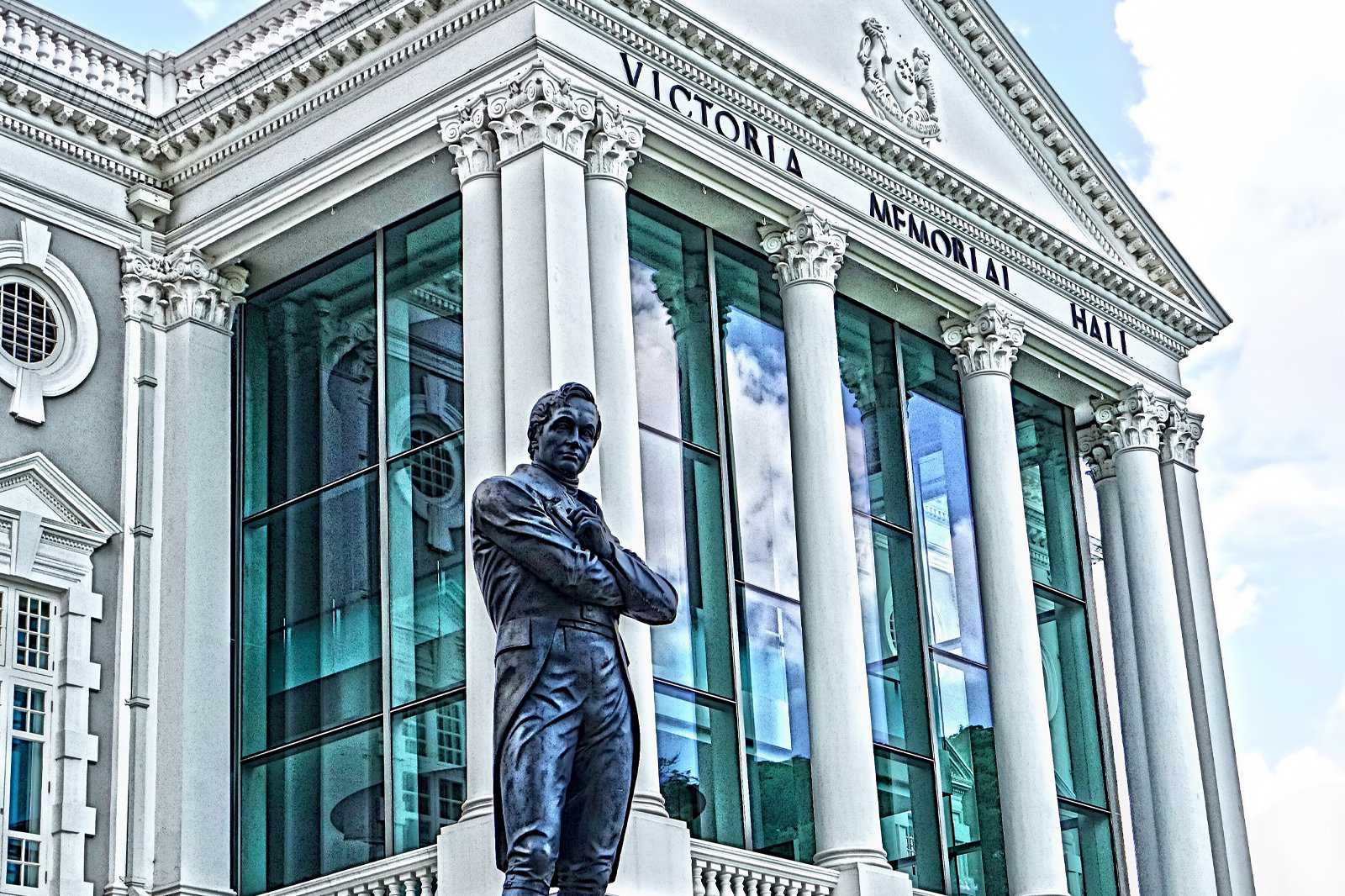

Stamford Raffles is often called the founder of modern Singapore. He gave shape to many sections of Singapore's city centre, which flourished as an important port and business centre in the region.

After the British secession of Dutch possessions in Southeast Asia, Raffles gained permission to establish a station in the region, to secure British trade interests there. He had initially set his heart on Riau, an island near Singapore, but the Dutch had already beat him to it. He then decided on Singapore, then under the empire of Johor.

When Raffles first landed in Singapore in 1819, there was a division within the Johor Sultanate. The old Sultan had died in 1812, and his younger son had ascended to the throne when the eldest son and legitimate heir, Hussein, was away.

Raffles threw his support behind Hussein, proclaiming him Sultan and installing him in Singapore. He also signed a treaty with the Temenggong, or senior judge, of Johor, setting him up in Singapore as well.

In so doing, he hoped to legitimise British claims on the island. Initially, Raffles acquired the use of Singapore after agreeing to make annual payments to Sultan Hussein and the Temenggong. In 1824, in exchange for a cash buyout, Singapore officially came under the ownership of the British East India Company.

Two years later, the island, along with Malacca and Penang, became part of the British Straits Settlements. The Straits Settlements were controlled by the East India Company in Calcutta but administered from Singapore.

Raffles initiated a town plan for central Singapore. The plan included levelling one hill to set up a commercial centre (today's Shenton Way) and constructing government buildings around Fort Canning.

Raffles, and the first Resident of Singapore, William Farquhar, gradually moulded Singapore from a jungle-ridden backwater with poor sanitation and little modern infrastructure to a successful entrepôt and colonial outpost. Hospitals, schools and a water supply system were built. Soon, boatloads of immigrants from India and China were coming to Singapore, in search of prosperity and a better life.

Today, you'll find that many institutions and businesses choose to use Raffles' name, out of certain respect or perhaps to portray a sense of history and gravitas. You will find the Raffles name linked to a boulevard, a school, a college, a hotel, a shopping mall, the business class of Singapore Airlines, a golf club, and a lighthouse.

Legend has It...

The beginnings of Singapore are steeped in local Malay legend. The island is said to have received its name from a visiting Sumatran prince in the 14th century, who saw a fearsome creature – later identified to him as a lion – on his arrival.

Taking this as a good omen, the prince founded a new city on the spot, changing the name of the island from Temasek to Singapura. In Sanskrit, "singa" means lion and "pura" means city.

Thus the Lion City was born, and today the symbol of the merlion – a mythical creature with the head of a lion and the body of a fish – is a reminder of Singapore's early connections to this legend and the seas.

The March of Empires

Traders travelling between China and India have been ploughing the waters around Singapore since the 5th century AD. Later, Singapore became a trading outpost of the ancient Buddhist kingdom of Srivijaya, which had its centre in Palembang, Sumatra, and influenced the region from the 7th to the 10th centuries.

In the 13th century, Srivijaya was overshadowed by the rise of Islam, and Singapore came under the influence of the Muslim empire of Malacca. Malacca, situated on the western coast of present-day Peninsula Malaysia, rapidly developed into a thriving free port and commercial centre.

Malacca's decline began in 1511 when it fell under the sway of the Portuguese. The Muslim merchants and traders that had founded the commercial success of Malacca fled from the new Catholic rule, and another, smaller sultanate established itself in Johor, at the southern end of the Malaysian peninsula, across the causeway from Singapore.

In 1641, the Dutch wrested Malacca from the Portuguese. They held power until 1875, when Holland's defeat in a war in Europe saw the British seizing Dutch colonies in Southeast Asia, including Malacca.

With the end of the Napoleonic wars in Europe, the British agreed to hand back Dutch possessions in 1818. Some British were disappointed by this anticlimax to their country's bid to expand its influence in Southeast Asia. One of them was Stamford Raffles, the Lieutenant Governor of Java.

Economically, Singapore went from strength to strength throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. But in the 1940s and 1950s, political storm clouds were gathering over Asia. Japan's quest for more power, land and natural resources saw it invading China in 1931 and 1937, a move which was opposed by the Chinese immigrants in Singapore.

On February 15, 1942, with Europe in the throes of World War II, the Japanese sprung a quick and successful invasion of Singapore. The British, who had prepared for an invasion from the sea in the south, were taken by surprise by the Japanese penetration via the jungles of Thailand and Malaysia (on bicycle). The British surrender was quick, and many of the Europeans were herded to the Padang, then sent to Changi Prison.

The next few years were a dark period in Singapore's history. The Japanese treated the Chinese with particular suspicion, and many of them were tortured, incarcerated and killed, often on the flimsiest of pretexts. As the war progressed, food and other essential supplies ran low, and malnutrition and disease were widespread.

By 1945 however, it was clear that Japan, and its allies, were losing the war. The Japanese surrendered Singapore on August 14, 1945. The British returned, but their right to rule was now in question.

Gaining Independence

After the war, the British grouped the peninsula Malay states and the British-controlled states of Sabah and Sarawak in Borneo under the Malayan Union. Singapore, which unlike the other states had a predominantly Chinese population, was left out of this union.

Rebuilding itself after the war was a slow and difficult task. In the post-war climate of poverty, unemployment and lack of ideological direction, communist groups such as the Malayan Communist Party and the Communist General Labour Union, and the socialist Malayan Democratic Union, gained popular support.

In the late 1940s, the Communists launched a campaign of armed struggle in Malaya, prompting the British to declare a state of emergency where the Communists were outlawed. Twelve years of guerilla warfare from the Communists on the peninsula ensued, and left-wing politics was gradually snuffed out in the Malay states and Singapore.

Lee's Legacy

In the 1950s, a rising star emerged in the local political scene – Lee Kuan Yew, who headed the socialist People's Action Party (PAP). Lee, a shrewd politician, is a 3rd-generation Straits-born Chinese with a law degree from Cambridge University. When the PAP won a majority of seats in the newly-formed Legislative Assembly in 1959, he became the first Singaporean to hold the title of prime minister.

In 1963, the British declared Singapore, the Malay states and Sabah and Sarawak as one independent nation – Malaysia. But Singapore's membership in this union lasted only 2 years. In 1965, it was booted out of the federation, owing to disagreements on several fronts including racial issues.

Left on its own, Singapore embarked on an ambitious industrialisation plan – building public housing, roads and modernising its port and telecommunications infrastructure. English was chosen as the official language, to facilitate communication between the different races, and to put the nation at the forefront of commerce.

In about 25 years, by the late 1980s, Singapore had moved from a fragile and small country with no natural resources to a newly industrialised economy.

Singapore History in Brief

The island of Singapore was first described by a 3rd-century account as "Pu Luo Chung", meaning "isle at the end of the peninsula". This description, would in the future, prove very offhand and unassuming, for even as Singapore entered the 14th century, it had gained might as part of the romantic, albeit tragic, Srivijayan Empire.

The "little island" was then known to many as "Temasek", which meant "Seatown". It was then the point where the sea routes of Southeast Asia converged; and the harbour where floating vessels of every kind, from Indian boats and Chinese junks to Buginese schooners, Arabic dhows and Portuguese battleships, visited.

Legend has it that as the winds of change blew into Temasek, a prince of Srivijaya paid a visit to the island and saw a lion. This wondrous sight so compelled him that he renamed the island "Singapura", meaning "Lion City". It didn't seem to matter that lions had never inhabited Singapore and that many believed he must have actually seen a tiger!

And so, Singapore's modern day name was born out of a sighting believed to be a good omen, and the region was established as a trading post for the Srivijayan Empire. In the 18th century, the British were searching for a harbour in which to refit, provide for and protect their fleet of vessels.

This harbour would also be a demarcation point to forestall the advances of the Dutch in Southeast Asia. Singapore's strategic location caught the attention of Sir Stamford Raffles, who then established Singapore as a British trading station in 1819, with a free trade policy to attract merchants throughout Asia, and even all the way from the Americas and the Middle East.

By 1832, Singapore was the centre for the government of the Straits Settlements of Penang, Malacca and Singapore. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 and the advent of the steamship expanded the trade between the East and West, and also Singapore's importance. Singapore continued to grow well into the 20th century until World War II when the freeport became the scene of the war's significant fighting.

The end of World War II saw Singapore becoming a Crown Colony, but the rise of nationalism put Singapore on the path of self-government in 1959. Singapore formed a union with Malaya in 1963, but opted for independence and became an independent republic on August 9, 1965, with Lee Kuan Yew as Prime Minister.

Singapore Today

Singapore today is a thriving centre of commerce and industry, with intense economic growth. Singapore is not merely a single island but is actually the main island surrounded by at least 60 islets. Measuring a compact 720 sq km, its size really belies its capacity for growth.

Singapore is now a rapidly developing manufacturing base. The Republic, however, still remains the busiest port the world over with more than 600 shipping lines herding supertankers, container ships, passenger liners, fishing vessels and even wooden lighters in its waters.

It is also a major oil refining and distribution centre, and an important supplier of electronic components. Its rich history as a popular harbour has turned it into a leader in shipbuilding, maintenance and repair. Singapore has also become one of Asia's most important financial centres, housing at least 130 banks.

Both business and pleasure are made more accessible and smooth flowing by the Republic's excellent and up-to-date communications network, linking it to the rest of the world through satellite and round the clock telegraph and telephone systems. Now fully grown into an Asian Dragon, Singapore is, somehow unsurprisingly, a leading destination for both business and pleasure.